The Mystery Ship -A Tragedy

See:Abandoned Shipwrecks Today Below!

by Andreas Jordahl Rhude

On July 29th, 1969 President Nixon was in Thailand on his way to visit Vietnam. Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins were still in quarantine nine days after Armstrong set foot on the moon. Senator Edward M. Kennedy was in seclusion after the Chappaquiddick tragedy. “The Courtship of Eddie’s Father,” starring Bill Bixby, was soon to hit the television airwaves and Woodstock was just days away. A fateful event took place that same day in the summer of 1969. It was hailed as a triumph of the year — the resurrection of an historic relic. A wooden schooner, the “Mystery Ship,” was raised from the depths of the waters of Green Bay. She had sat on the floor of the bay for 100 years and was now seeing daylight for the first time in a century. The spectacle received nationwide media attention. It was the culmination of two years of tireless effort of a small crew of men. But alas, her fate was one of ruin, and it was a fate predicted by one man with expertise in wood.

So

how was the Mystery Ship rediscovered? It was all coincidence. In November 1967, a commercial fisherman’s nets became tangled in an object at a depth of 40 feet near Chambers Island in the waters of Green Bay. Charts indicated that the depth at the same location was 105 feet. The fisherman, wanting to salvage his costly nets, hired a scuba diver to free them. That diver, Frank Hoffman, found the nets tangled in what amazingly appeared to be a ship’s mast. Diving deeper, he found an ostensibly intact ship at a slight list on the clay bottom of Green Bay.

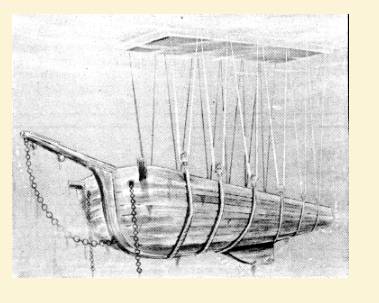

This underwater sketch shows how six powerful cables were rigged to the Alvin Clark at its grave site in 110 feet of water. The cables were hooker up to a barge on water where men and women controlled winches that slowly lifted the 218 ton ship to the bottom of the barge for its underwater journey to Marinette.

Hoffman, a veteran diver, was familiar with ship salvage operations. He investigated the ship through additional dives and learned that the wooden hull was indeed intact. Both masts were still upright and in good condition. He figured she could be raised to the surface and possibly even be rigged for sailing once again. He kept his discovery secret and by early 1968, he had secured the federal salvage rights. During the summer of 1968, Hoffman and his fellow divers slowly recovered artifacts from the ship. They were carefully removed and then cataloged by James Quinn, director of the Neville Public Museum in the city of Green Bay. Some of the items found were the captain’s writing desk, a brass locket, a wallet, clay pipes, a water pitcher, a clock, an oil lamp with patent date of August 11, 1863, tools, and three pennies. Even a crock of cheese – still full, was pulled from the ship! Divers could only be in the water for about fifteen minutes at a time due to the cold water temperatures hovering around 40° F. It was a painstakingly slow process.

With the assistance of ship builders Harold and Jim Derusha of Marinette Marine Corporation, Hoffman and his crew began the complicated task of bringing the Mystery Ship to the surface. In 1968, they placed steel cables beneath the ship. They used compressed air to bore holes through the mud under the ship so that the cables could be jimmied in. About ten tons of silt was pumped  out of her holds. The plan was to use a barge with hand winches to lift the ship off the floor of the bay. They would then lift her up to within 40 feet of the surface and slowly ease their way towards shore. When they got to a water depth of about 40 feet, they would set her down to adjust the slings and make final preparations for bringing her to the surface.

out of her holds. The plan was to use a barge with hand winches to lift the ship off the floor of the bay. They would then lift her up to within 40 feet of the surface and slowly ease their way towards shore. When they got to a water depth of about 40 feet, they would set her down to adjust the slings and make final preparations for bringing her to the surface.

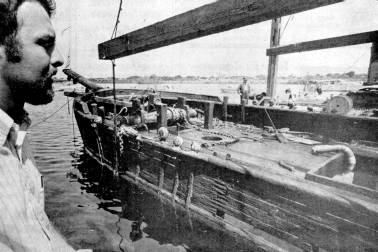

The Mystery Ship, towed to Menominee Marina for the Blessing of the Watercraft ceremony, proved to be a big draw. A record 30,000 persons attended the annual even in 1969.

The shipyard of Marinette Marine became the destination for the final raising. Located about one mile inland from Green Bay on the Menominee River, the company proved to be an invaluable contributor to Hoffman’s efforts. They let him use an LCM6 (landing craft medium) built by the firm during the summers of 1968 and 1969. Marinette Marine also arranged to have the two 130′ x 30′ barges made available for the raising. On July 23rd, the vessel was successfully lifted off the bottom, 19 fathoms deep. Starting at 4:00 a.m., the crew worked till 9:00 p.m. to lift her and tow the entire rig towards shore. At times, members of the news crew that were on hand pitched in to relieve the salvagers. Most of the cranking of the winches was done by hand! As the day progressed, squalls kicked up causing even more anxiety. The week before, the two masts were lifted to the surface and brought to the Marinette shipyard. They were found to be in excellent condition. While all this was occurring, the identity of the ship was still a puzzle, thus the name “Mystery Ship” was attached to the effort. She was later identified as the “Alvin Clark” through contemporary newspaper accounts, national archives, and U.S. Coast Guard records. A stencil found on the ship was positively attributed to one of the sailors on the Alvin Clark — Mr. Michael Cray of Toronto — one of the two survivors of the sinking.

The final lifting took place on Tuesday, July 29th, 1969, at the Marinette Marine docks. About 4000 spectators (including the author of this article!) were on hand as she was lifted from her watery grave. Four cranes, two on the docks and two on a barge, began lifting at 10:24 a.m. and soon the bowsprit was above the water’s surface. Cheers from the crowds and horn blasts from spectators in their boats rang out as soon as the bow emerged. After being pumped out of water and silt, she floated on her own!

Just over one week after she was raised to the surface and her holds cleaned of the silt, she was towed to the Menominee harbor. She was on display during the annual blessing of the fleet on August 3rd. An estimated 30,000 people saw the 122 year old relic. It was a happy day for those responsible for bringing her up from the sea bottom.

The “Alvin Clark” was a lumber schooner owned by Captain William M. Higgie of Racine, Wisconsin. The ship was running empty and she was under full sail heading to Oconto on June 19th, 1864, when she capsized in a sudden storm just off the shores of Chambers Island. The Civil War was raging in the east and southern parts of the county at that time. Built near Detroit, Michigan in 1847, the Alvin Clark was 105 feet in length, had a beam of 25 feet, and displaced 218 tons. She was rigged with two masts. Her foremast was square rigged, placing her in the brigantine class.

To insure that the ship would not be torn apart while drying out after being in the water for 100 years, an enclosure was built around the ship. It was a makeshift dry-kiln used to dry her out very slowly. Over the winter of 1969-1970, she was slowly dried out, cleaned up, and ultimately put on display in Menominee, Michigan at the Mystery Ship Seaport.

To insure that the ship would not be torn apart while drying out after being in the water for 100 years, an enclosure was built around the ship. It was a makeshift dry-kiln used to dry her out very slowly. Over the winter of 1969-1970, she was slowly dried out, cleaned up, and ultimately put on display in Menominee, Michigan at the Mystery Ship Seaport.

The Alvin Clark– back from its watery grave.

The biggest hurdle overcome by Hoffman, so he thought, was the actual raising of the relic from the sea bottom. As it turned out, insurmountable problems began once the ship was floating again. The ship was towed across the river to Menominee and put into a slip. Along with the artifacts displayed in a museum building, she became a tourist attraction. The entry fees were no where near enough to pay for the original salvage or for the upkeep of the ancient vessel. Hoffman offered to sell the ship to Menominee. When they balked, he sought buyers in other ports of the Great Lakes. In 1976 Hoffman said, “Our number one goal right now is to preserve and take care of the ship.” He continued, “This ship is a piece of Great Lakes history. It tells us now and it will tell generations later what the pioneer lumber and sailing era was all about. People and organizations spend all kinds of money to build replicas of ships that don’t have nearly the historic value of the Alvin Clark and we can’t get a dime to preserve this ship. I don’t understand it.” However, with no funds, nothing was done to insure a long life for the ship. Hoffman sold the ship in 1987 to a group of local investors. They too, failed to preserve the ship.

The ship was well-preserved in her watery grave for 105 years. Why? In order for wood to decay, four elements are required: oxygen, a favorable temperature, a food source (the wood itself), and moisture. If one of the four is eliminated, wood will never decay. The cold water temperatures of Lake Michigan, along with a lack of oxygen, ensured that the wood of the Alvin Clark would not decay. Water action and movement of sand did, naturally, weather the wood surfaces to a certain extent. But because she did not break up while sinking, and her hull was intact when brought to the surface, she was able to float again on her own.

Once exposed to the air and temperatures favorable to rotting, it was just a matter of time before she succumbed to decay. Measures were never taken after she dried out to protect the wood against decay. And for this reason, it was only 25 years for her to become decayed beyond repair. The resurrection of the ship was a feat uncommon to man and it was hailed as a triumph of maritime heritage. However, there was never any plan for the disposition of the ship or for its protection.

What became of the Mystery Ship? Her ultimate fate, a sad one, was predicted before the ship even saw the surface of the water. On February 26, 1969 the wood expert wrote: “It would be better that the mystery ship, the logging schooner, remain in her watery grave where she has been preserved all these many years, than to have her lifted ashore and go to ruin. The cost to bring her ashore is one thing; the cost to preserve her is quite another. 2 These words, probably read with little enthusiasm at the time of their writing, were to come true.

In May of 1994, the remnants of the Alvin Clark were demolished with a bulldozer. She was rotten beyond hope of saving and her owners were broke. The dream of Frank Hoffman faded with no ceremony. The ship sat below the surface of the chilly waters for more than a century, but it took only twenty-five years of being above the surface for her to succumb to the elements. It was a sad and tragic ending to the life and resurrection of the SS Alvin Clark, the ship that had a second chance at life.

Although the ship is gone, the museum of artifacts still operates as the Mystery Ship Marina and Museum. It is located on the Menominee River in downtown Menominee, Michigan.

1 Sources of information for this article include: authors personal recollection: Marinette Eagle-Star; Menominee Herald Leader; Peshtigo Times; Green Bay Press-Gazette; Milwaukee Journal.

2 Letter from Maurice J. Rhude to Jim Lieburn, February 26, 1969, In possission of the author.

ABANDONED SHIPWRECKS TODAY

by Andreas Jordahl Rhude

What would have happened if the Alvin Clark had been discovered in 1989 instead of twenty years earlier? Current federal and state legislation, for the most part, prevents the surfacing of old shipwrecks. In 1987, the federal government passed a law, the Abandoned Shipwrecks Act, which regulates underwater archeology sites, specifically shipwrecks. It states that an abandoned ship is property of the state in which it lies. To qualify as an abandoned ship, two criteria are necessary: it must qualify for the National Register of Historic Places (i.e. be at least 50 years old,) and it must be embedded in the sea bottom to a certain extent (indicating that she had been on the sea floor for some time). The reason for this type of legislation is to prevent the type of tragedy that occurred to the Mystery Ship.

The state of Wisconsin enacted a law in 1988 which provides funding for the State Underwater Archeology Program, administered through the State Historical Society and the DNR. It is a means to study underwater archeology sites and improve management, and to create underwater preserves for resource protection.

According to a source at the State Historic Preservation Office of the Minnesota Historical Society, a case in point is the streetcar boat Minnehaha. If she were discovered on the bottom of Lake Minnetonka today, she probably would remain there. Unless the salvagers proved that they had committed financial resources as well as a salvage and restoration plan, the state would prevent the operation. When the Minnehaha was originally raised from the bottom in 1980, she was towed ashore and she sat and rotted due to no provisions by the salvagers for her maintenance. Ultimately, she was restored and now plies the waters of Lake Minnetonka, but only after a costly restoration — much more costly than if she had been worked upon soon after her raising.

The reasons for such laws are to protect these unique cultural resources for the good of all citizens. Even though the Minnehaha was ultimately a success story, more often, a tragedy takes place such as occurred with the Alvin Clark.